Imperfection and Subjectivity

Deformation as liberation. The rot that determines what is The Real.

The obsession with perfection seems to be a fixture in society and civilization. That want for the desireless form, something that lives up to what could only exist in the human mind. This want and desire, the disgusting force that drives us onward in history, yearning for an absolute. The absolute never comes; the desired form is achieved, but as soon as perfection is reached, it is undesirable; the most perfected form of something loses its perfection as soon as we are engaged. Our perception is imperfection, tainted by desire. Desire, this wellspring of neurosis, haunts humanity, so we desire to escape it, to become an object in the eyes of others, to become removed from the self. The idea that this is achievable in the unmodified human psyche is laughable. No amount of meditation, gnosis, or whatever other transcendental revelations that come to you will free you from desire’s grasp. We are bound to our physical programming; only the most extreme forms of self-mortification can begin to change that base.

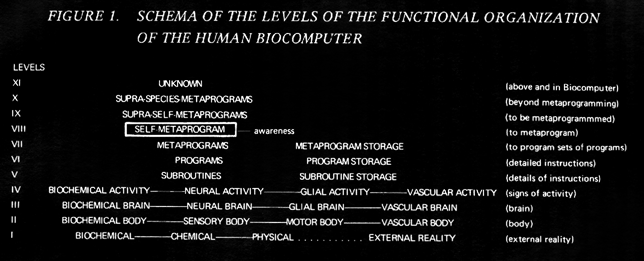

The limitations of human hardware make reaching a desireless form near impossible, but the answers lie in two places if one wants to get a state of objectivity. Metaprogramming and lobotomy are those answers, the former being John C. Lilly’s dive into the human mind using LSD. I am loathe to rely entirely on a psychonaut after deriding Gnostics and Ascetics earlier. Still, Lilly’s usage of LSD to break the psyche and to try to reform it is valuable to explore, even if it does not overcome the issues of hardware. Its theoretical basis is the complete separation of the body and the mind, where the psyche is just a vessel inside flesh; the mind can be disassociated from the body, but the mind cannot depersonalize from itself.

The most base part of the psyche, the programs and subroutines, that dividing line between the body and the “soul” and the usage of LSD to access “higher levels” through the door and key method, which in brief is visualizing the psyche as a bunch of doors that store the parts of the personality, subroutines, programs, metaprograms, et cetera. This allows for limited modification to the more base metaprograms, the ones not contained under awareness, or Self Metaprograms, the actions we consciously take.

Lilly directly states in Programming and Metaprogramming the Human Biocomputer that the metaprogramming language is unique to the individual. He discusses the language's incommunicability: “This language is not all shared in the usual public domain of the language acquired in childhood.” the inability to share the subjective experience with another person through how our software is. The individual and their emotions are nearly impossible to fully define in language; we can only get close to it, so when we look internally at metaprogramming, it allows the individual to tamper with their subjectivity. This does not cure or remove that desire, the drive for the perfected self, but is offered by Lilly as a way to close in on the more “perfected” self.

Realistically, this is just a way to traumatize your psyche, to break it over your knee, and to reduce yourself to more base instincts, tampering with the “higher” mind in hopes of curing neurosis. LSD does not eliminate desire; the process of metaprogramming, even if you can lessen some neurosis or contradiction, does not change desire nor get you anywhere close to perfection. Neurosis in and of itself is not imperfection; it’s a feature of the psyche; it serves as this byproduct constantly belched out by the cycle of desire and want. Without changes to the “hardware,” you cannot escape desire; even the Icarian ideations of transhumanism cannot save us from desire. At most, we will see a dreaded liberation from death, the end of life having value. The brain will be locked into the cycle of desire forever without end, perpetually wanting and screeching out to the void to be made whole.

Real transhumanism has already come to pass to eliminate this desire by going to the root source. The act of slicing into brain matter is liberatory. Freedom from the higher self, the divorcing of the body from this idealist mind, one that cannot honestly know the world. This is as close as we can get to perfection, the liberation from the mind, but we cannot even fathom it. Our imaginations, even if we forced a “simulated experience” with whatever psychedelics, cannot fulfill a complete liberation; our subjectivity always returns in some form, and the ego refuses to shrivel up and die.

Our wings melted, we hurdled towards the sea, and as soon as the water broke, we tried again. We wanted to find some way to reach perfection, to eliminate our neurotic subjective minds. But we would never reach it. A lobotomy means we lack the subjectivity to experience our perfection, so it is all for naught, and metaprogramming is just a way to try to castrate the mind. The natural path, not to perfection but to acceptance, is recognizing the material base, even though we can never fully perceive it. Our psyche protects us from The Real, the actual material world. By just acknowledging that we have no sense of objectivity or order, we can begin to understand our functions, our subconscious motivators, our neurosis, and its source, our desire. The recognition of how our subjectivity informs our worldview and ties back to every program, metaprogram, and subroutine, eventually bringing it back to our hardware, the limitations of flesh.

That base desire, that want for ideal forms, it is hardcoded into the subject. Humanity yearns for perfection, externally and internally, the want for a perfect world, system, and soul. The closer we as a species march towards “perfection,” the more our ideals succumb to entropy; the once beautiful woman in the distance, as we close in, becomes a putrid rotting corpse. The miasma from the body is enough to dissuade us from wanting it anymore; the new perfection needs to be imagined. There is no appreciation for the maggots that crawl, the smell of old blood, and the disgusting truth that lies in front of us. We are just fixtures; our subjectivity is a blinder, and it stops us from seeing our place as a blip on the map. In the grand scheme of history, we are nothing; people think of this and become pessimists, shackled to some false sense of destiny, but they should feel truly liberated. We only need to do so little to make our blip last; the smallest of etchings, the most basic items we keep with us, may last millennia to be found. The same projected ideals we have on our ancestors will be applied to us.

But the blip will never be appreciated in our day and age. We live in the era of ideology, where the predominant liberalism calls to us and informs our subjective worldview that we need to make our mark. That mark must be made either in action or reaction by being someone who matters, feeding into libidinal desires and associations. Our subjectivity is so malleable and easy to break and mold but impossible to cure; the most superficial ideological formations can draw us in like moths to a flame. Inching ever closer before our internalized sense of self is informed by only what we consume.

It is hard to remove oneself from ideological conceptions, even when trying to grapple with the fact that the world is just is. We have become accustomed to ideological conceptions because it is the only way to give ourselves meaning and a sense of narrative. There is no past or present. Time, as we know it, is a creation of the subjective, trying to give itself a narrative of A to B to C. Everything that can be perceived is something we cannot take at face value; our psyche betrays us at all moments, filtering the world in a way that is safe to it. Our genetics have predisposed us to this prison of flesh, where we will never truly know the external world. The Ascetics and their attempts to abandon all that is worldly fall short because there is only the world.

The other attempt to exalt oneself in the material world through consumption, an utter giving into excess, often falls short for similar reasons. The subjective mind focuses on what’s being consumed and the act of consumption, not on the material world. Vapid consumerist materialism is no cure; it is a reification of consumptive identity, the ideology as a spirit inside every commodity the individual engorges on.

Perfection is impossible, and the constant movement of desire prevents us from being comfortable with whatever inkling of the ideal we bring to the world. Desire, as a consequence of the blinding psyche, cannot live with the world as it is. We exist only in the realm of the material base, The Real, but we are blocked from perceiving the world as it is. The only access to this material realm is traumatic acts, and that is in brief. The only way to become a desireless object and enjoy perfection is the mortification of the mind, the removal of subjectivity with a hammer and chisel. The ego, the everpresent I, will never be satiated; its desire for self-objectification can never be reached. The mewling for a place in objective history goes unheard as the world goes on uncaring after the subject’s demise, their body, putrid, having long succumbed to decay.

I don't want to be perfect. That would be utterly boring. I'm a minimalist. Moving around the country quite a bit made me not want to accumulate crap that I don't need to survive. Books are grand 💕 But moving a large collection of them sucks donkey balls. Lol.

Isn't this why we continue to experience progress in the world: that not one person, or even a generation can determine, and effectively stay the hand of progress? I think this is something good.